This is the everything you wanted to know about Mirin page. It answers: Where did Mirin come from? How is Mirin made? How does Mirin improve food? When should Mirin be used? What are the types of Mirin? What is the difference between Hon-Mirin and Aji-Mirin? Why is some Mirin light and others dark? What can I substitute with Mirin?

History of Mirin

Mirin started out as a popular sweet liqueur for women in medieval Japan. During the Edo period, the first sugar cane plantations were still 2 centuries away. Nipponese cooks from the era found Mirin to be an excellet form of sweetness and incorporated it into many of their recipes. With the Meiji Restoration, Mirin as a drink went out of vogue like the samurai, but Mirin as a flavouring agent went from strength to strength. Today Mirin has become an essential part of culinary Japan and at least one bottle of it can be found in every Japanese kitchen. So if you have ever wondered why the miso soup you made at home doesn’t taste as good as the ones from the restaurant – the missing secret ingredient is probably Mirin.

Brewing Mirin

Mirin was, and sometimes still is, made by introducing Sochu to the vat halfway through a quasi-sake brewing process. The Sochu(a vodka-like spirit) kills all the fungus in the fermenting rice (Koji) which would otherwise metabolize all the sugars. This is not dissimilar to the procedure where Brandy is added to half-fermented wine to give us Port. Although Mirin and Sake are made from different types of rice, the similar initial brewing process imparts to Mirin some of the tastes reminiscent of Sake but that is where their similarities end. The alcohol content in Mirin is lower at somewhere between 12-14%. Because Sochu is added, complex sugars and proteins form as Mirin is left to mature, giving it its distinctive sweet taste and golden colour.

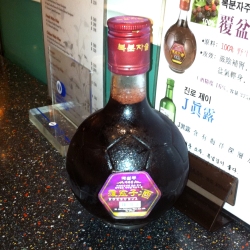

Mirin slowly darkens from a golden colour to a deep amber colour as it ages. Amber-coloured Mirin has an additional caramelized flavour from the slow oxidation process so don’t think that its going bad. It looks black in the photo because you are looking through 2 inches of the amber Mirin, if you pour it out onto a spoon you’ll see its true colour. I added a bottle of unopened Hon-Mirin to the top picture just to show you what virgin Mirin looks like. Keep your Mirin refrigerated after it is openned as the cap tends to get moldy after some time in a hot humid climate.

Varieties of Mirin

Mirin comes in three qualities. First there is the good stuff that is brewed in the traditional manner, as described above. No artificial additives or preservatives are added. This type of Mirin can be drunk like Port or Madeira and it takes perhaps 2 years before the Mirin can be bottled. The manufacturer will often state somewhere on the bottle that its product is authentic Mirin. Koji (or malted / fermented rice) is always one of the ingredients on the label on the back, and they often tell you which area the rice was harvested from. Also, when it comes to Mirin there is no better quality assurance than a glass bottle.

Then there is the  mediocre factory stuff, a synthetic Mirin, manufactured using enzymes on rice in a high temperature / pressure process. A batch of this type of mirin takes only about 3 months to make and it invariably comes in a plastic bottle. You can always judge Mirin quality by checking the ingredients at the back; some tell tale ingredients of synthetic Mirin are corn syrup, glucose syrup and alcohol (instead of shochu). There is a popular brand of Mirin called Hon-Mirin, which ironically translates as real-mirin, but it is not the real McCoy. There is another sub-type called Aji-Mirin, which means tastes-like-mirin. Many people think that Aji-Mirin is inferior to Hon-Mirin but they are exactly the same thing except a little salt has been added to Aji-Mirin so it is not subject to alcohol tax. The ingredients for both types are practically the same except for the salt. Since you are cooking with it, a little salt won’t matter, so don’t get hung up about whether it is Hon or Aji; both are equally mediocre.

mediocre factory stuff, a synthetic Mirin, manufactured using enzymes on rice in a high temperature / pressure process. A batch of this type of mirin takes only about 3 months to make and it invariably comes in a plastic bottle. You can always judge Mirin quality by checking the ingredients at the back; some tell tale ingredients of synthetic Mirin are corn syrup, glucose syrup and alcohol (instead of shochu). There is a popular brand of Mirin called Hon-Mirin, which ironically translates as real-mirin, but it is not the real McCoy. There is another sub-type called Aji-Mirin, which means tastes-like-mirin. Many people think that Aji-Mirin is inferior to Hon-Mirin but they are exactly the same thing except a little salt has been added to Aji-Mirin so it is not subject to alcohol tax. The ingredients for both types are practically the same except for the salt. Since you are cooking with it, a little salt won’t matter, so don’t get hung up about whether it is Hon or Aji; both are equally mediocre.

Finally there is the terrible stuff, something called Shin-Mirin which translates as new-Mirin. This is basically a mirin-flavoured sauce with almost no alcohol content, another even cheaper way to get around the alcohol tax. I’m sorry I don’t have a bottle handy to photograph. Do not bother with Shin-Mirin unless you have a phobia thing about alcohol. Once you heat Mirin, any remaining alcohol will evaporate anyway.

Cooking with Mirin

In Japanese cuisine, Mirin is commonly used in simmered (e.g. Oyakodon) and stewed (e.g. Chashu) dishes. It is basically used each time you want to balance out soya sauce or miso based dishes. You can pretty much make teriyaki sauce by mixing Mirin with sugar and soya sauce. Mirin is also added to vinegared sushi rice and sesame salad dressing.

When do I use my quality Mirin and when do I use factory Mirin? If the Mirin is to be consumed directly, say like in a salad dressing, I will use my good stuff. Likewise if the recipe calls for small amount of Mirin, like a tablespoon that is added to soup. If the recipe calls for Mirin by the cupful, for example when I are stewing pork, then I will use my synthetic Mirin.

What about using Mirin when it is not specifically mentioned in the recipe? Whenever your recipe calls for a teaspoon of sugar, try using a tablespoon of Mirin instead. Sugar does nothing but make your food sweet but Mirin will help to accentuate the milder flavours. The key is to only use it in limited quantities since it has quite a strong distinct flavour. Mirin is known for its glazing characteristics so you can paint it on seafood prior to grilling. Speaking of seafood, Mirin is also prized for its ability to counteract fishy and gamey smells, so you can often add a tablespoon to your marinades. Finally whenever your recipe calls for a dash of Port or Sherry, try substituting Mirin instead. I sometimes add a dash to my tomato or cheese based pasta sauces/risottos.

Substituting Mirin

In an emergency, in place of Mirin you can use a Sake plus honey (or maple syrup) substitute. Mix 5 parts of Sake with 1 part of honey, then heat the mixture until it is reduced in volume by half.

Additional Information

Some sites of Mirin manufacturers with detailed information

If you liked this post on Mirin, you may also be interested in my post on its savoury complimentary, Chinese Cooking Wine.